Reflections on old music

“If you know where you came from you can better understand where you are going”.

I have heard this saying used many times over the years. As I sit at my desk casting around for inspiration, I remember one of the UK’s most well known MD’s, as he hands out dusty, yellow music, repeating this to us. Again.

I’m fortunate enough to have grown up in The Salvation Army and learned to play in my Corps band, before later becoming heavily involved in (what is affectionately referred to as) ‘outside banding’. The similarities are many, but one interesting difference I’ve observed is the attitudes to older music.

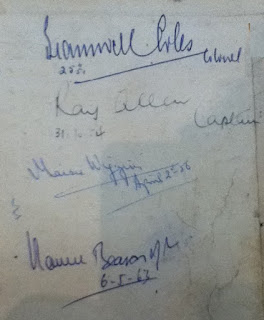

Time and again I’ve heard the collective groan in a non-army band room as a piece of music that is so old you almost need to wear white gloves when handling it is passed out. By contrast though, there seems, in my experience, to be a collective love for older music within the Salvation Army. Composers such as Eric Ball, Leslie Condon and Erik Leidzen are remembered fondly and newer music compared to the works of these greats. That’s not to put down modern composers by any means; within The Salvation Army there seems to be a clearer and more tangible thread flowing from old to new music and to be compared to Ray Steadman-Allen is nothing but the highest of compliments.

Time and again I’ve heard the collective groan in a non-army band room as a piece of music that is so old you almost need to wear white gloves when handling it is passed out. By contrast though, there seems, in my experience, to be a collective love for older music within the Salvation Army. Composers such as Eric Ball, Leslie Condon and Erik Leidzen are remembered fondly and newer music compared to the works of these greats. That’s not to put down modern composers by any means; within The Salvation Army there seems to be a clearer and more tangible thread flowing from old to new music and to be compared to Ray Steadman-Allen is nothing but the highest of compliments.

Perhaps this is because The Salvation Army is, for good and bad, a fairly small community where you don’t have to look far to find someone who is related to one these famous Army musicians. Maybe we wear red yellow and blue tinted spectacles, and maybe it is because some of these great composers were, quite simply, ahead of their time and what is ‘old’ music in terms of when it was written doesn’t sound out of place today. It is after all only nine years ago that Eric Ball’s masterpiece Resurgam, a piece written in 1950, was used at the Areas.

So, what is it then that causes the collective grumbling when old music is brought out in practice? I could probably use this question as the basis of an ethnomusicology dissertation such is the huge scope for detailed answers. It cannot possibly stem from any lack of technical or musical ability? Was it because, from its earliest days The Salvation Army has had a clear identity whereas ‘outside’ brass bands came together from a disparate and diverse range of industries, movements and hobbies which is reflected in its music? Or is does it come down to the mentality of the players – because there are not the same personal connections to the composers, it is not long before banding moves on to the next hot prospect? It is interesting that composers such as Peter Graham and Paul Lovatt-Cooper who have had great success and long-lasting impact have, however tenuous, links to The Salvation Army. Does the brass banding movement give its historical figures the credit they deserve?

I have been incredibly fortunate over this lockdown period to be able to have conversations with some incredible people involved in the brass band movement. Just speaking to some of these people is inspirational and it’s amazing that I’ve been able to share some of their stories with you through the medium of the blog. The feedback has been amazing and I have some more fascinating interviews lined up that will start dropping in the coming days – keep an eye out for these!

Comments

Post a Comment